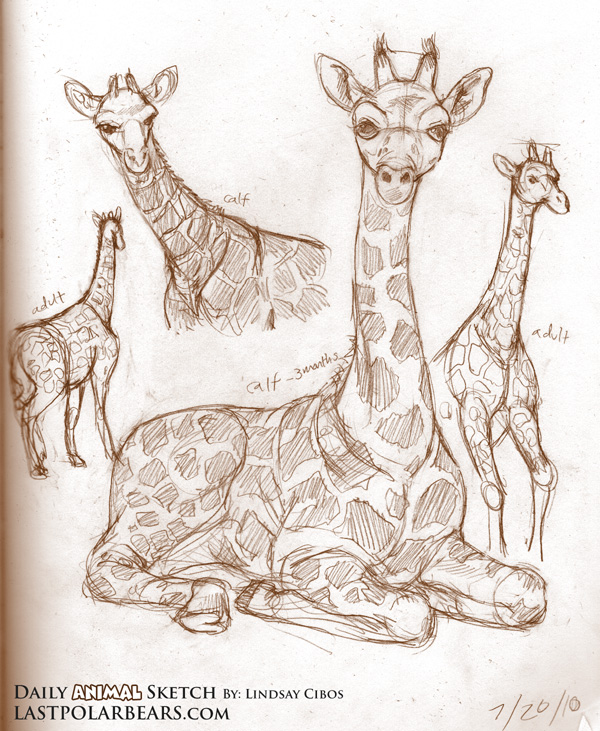

Studies of a giraffe adult and calf.

If you’re drawing a comic or an illustration with an animal in it, it’s important to have some degree of familiarity with the animal. The more comfortable you are with drawing animals, the more natural it will be to draw expressive animal characters, and having expressive characters is essential for any story.

Before I drew the first page of The Last of the Polar Bears, I spent months sketching polar bears (and arctic foxes, wolves, etc.) daily to build up an internal catalog of body language and movements that I can call upon when drawing pages. My first polar bear sketches were rough and awkward, as I groped to understand bear anatomy, but the more I drew, the more I improved.

So how do you improve your animal drawing skills when you’re working with a subject matter to which you don’t have direct access? I certainly don’t have a polar bear walking around my apartment. Aside from zoos (a great place to sketch and study animals), here’s a list of other resources that I use for drawing animals:

Books on Animal Anatomy

When learning to draw a new animal, I recommend drawing the underlying skeletal and muscular structures, at least once or twice. It will give you a greater appreciation for how the animal works underneath the hair and skin.

|

Cyclopedia Anatomicae by Gyorgy Feher and Andras Szunyoghy – This is a *really* neat book. It contains 600 pages of detailed drawings of complete skeletal and muscular structures for the human body, and a number of animals (including a 10 page section on bears), and their anatomical terms (knowing the scientific names of body parts aren’t necessarily essential for artists, but they can help give extra clarity when comparing the anatomy of different animals). |

|

Video Footage

Studying your animal subject in motion is essential to drawing believable body language and movement. Animals at the zoo can give you a good face-to-face sense of their physical structure, but being in captivity can effect their natural mannerisms. For this reason, it’s also important to observe how the animal operates in the wild. The Disney animators working on the Lion King spent weeks in Africa, sketching lions. Likewise, it would be wonderful to travel to the Arctic to observe polar bears, but that’s not entirely practical for an artist on a limited budget. This is where video footage comes into play.

BBC Motion Gallery – This is a great online archive of video footage of every subject matter you can think of. I love to put on videos of polar bears and arctic foxes, and freeze-frame the video to sketch the animal in a sequence of motion. It allows you to think about the positioning of their body as they walk, run, climb, sleep, eat; how many feet are planted on the ground at any given moment, and so on.

YouTube videos – There’s also some good stuff on YouTube, if you dig for it. Not my favorite resource, however.

Polarcam – San Diego zoo’s PolarCam offers great around-the-clock live polar bear footage in HD. It’s really fun to watch the bears ample around, sleep, play, and eat. The only caveat is that these are captive bears, so again, their range of activities and behavior differs from wild bears.

Photos

Not as helpful as video, but a good resource for studying body structure. It always helps to look at pictures of the real thing. My reference library of photos comes from all over the place. Personal photos taken on zoos and trips, or just random photos snagged off the Internet. It’s important to note that if you’re referencing photos (or videos) that aren’t yours, you shouldn’t use them directly in your illustrations without the permission of the copyright holder. That said, they’re great for practice sketching or double-checking your work (e.g. can a polar bear swivel its neck around that far? Aha, yes, here’s a photo of it doing just that).

Zooborns – This is a fantastic site. Not only does it give me a daily dose of cute baby animals, one of the highlights of my mornings (another is my morning cup of coffee), it gives me a unending source of animal photos and videos for daily practice sketching.

Those are the resources I use. Hopefully there’s enough on this list to get you started. You can see all of my daily animal practice sketches here. I’ll talk about making the leap from drawing realistic animals to expressive characters in a future post. In the meantime, remember: practice makes perfect, so start a sketch book, set aside time every day to draw, and get sketching. Good luck! 🙂